Nature is not a new topic for artists.

Ever since the cave paintings of animals, humans have expressed deep interest in nature. Great landscape art evokes a sense of wonder with the scenes unfolding in front of the viewer. For me, the greatest interest lies in studies that place forces of nature in opposition. Generally, the work of the Hudson School captures this conflict for me.

Now, with the climate crisis, art is representing the conflict between the results of human activities and the forces of nature.

Toward this end, an Internet list entitled “Arts and Climate Change” investigates and informs readers of new and imaginative ways to understand the crisis at hand – through created works in various media that extend knowledge in a meaningful way.

See & share: https://artistsandclimatechange.com/

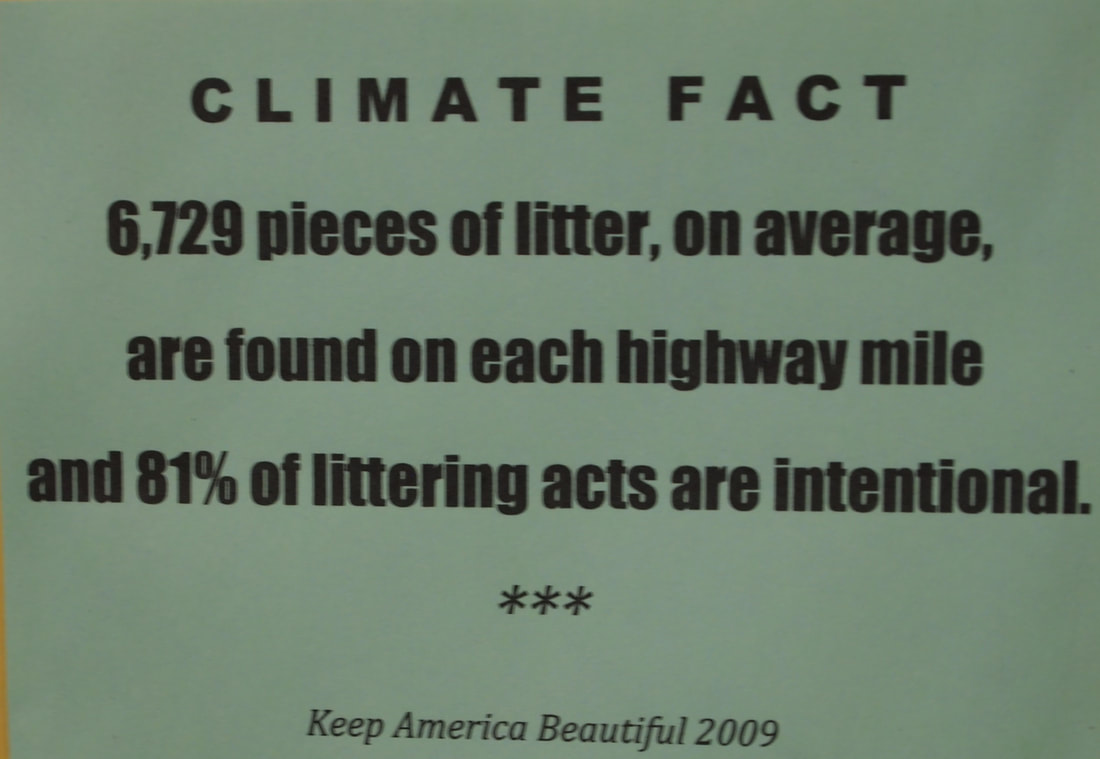

There also is a current exhibition, “One Tribe on One Planet,” at the Yocum Institute in West Lawn, Pennsylvania, presenting the artists’ conceptualization of this conflict very well. At the exhibit, one can see knowledge being absorbed or deepened on the part of the viewer. The exhibit designers interspersed sourced “Climate Facts” among the artworks, facts that relate to subjects of the pieces. This was powerful. (Exhibition open through June 27, 2019) Sometimes art, even when portraying a disaster, can be quite beautiful. The fear I had with portraying climate crisis is that beauty would undermine the message. My concern was unwarranted.

Over fifty years ago Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring, a scientific study of the impact of humans on nature, especially due to the indiscriminate use of chemicals through herbicides and insecticides. Carson’s work is still powerfully articulate. Afterwards, in 1989, Bill McKibben wrote The End of Nature. McKibben’s thesis is that humans are impacting all aspects of nature and that the idea of natural forces acting alone is no longer true.

More recently, David Grinspoon wrote Earth in Human Hands: Shaping Our Planet’s Future (2014). Grinspoon posited an idea of a new geologic phase of earth history, “one in which the net activity of humans has become a powerful agent of geological change equal to the other great forces of nature that build mountains and shape continents and species.” The emerging term for this new epoch is ‘Anthropocene’ or ‘the age of humanity (x)’.”

A common theme of these works is that humans can learn about forces affecting the planet and could take actions to slow, halt, potentially reverse, or adapt to the trend.

Reversing the trend will take knowledge and the will to act on that knowledge. Scientists have established undeniable facts about the climate crisis. Reports are issued almost daily in a torrent of studies that attest to the changes taking place and the process of measuring those changes.

Simply being willing as a scientist to learn about global warming, rising sea levels, species extinction, pollution, etc. is insufficient. Science can be complex and confusing to the non-scientist. It takes the arts to translate scientific observations and projections into forms that can be understood by non-scientists. The target is essentially on modifying human behavior. But the appeal is also to the general population, a voting population, that can generate the collective political will to act.

Scientists can measure the levels of CO2 in the environment to specific parts per million and calculate dangerous thresholds that are rapidly approaching. The artist can interpret the findings and present them in visual, literary, or musical forms. The arts, then, are vehicles to communicate to the public the knowledge distilled through scientific measurement and experimentation.

With over thirty works of art in various media, the message of the “One Tribe on One Planet” exhibition was unambiguous. Each work examined various impacts of humans on nature.

The artwork ran the range of concrete to abstract. Among the most creative was the work entitled “No Fish” by artist Melody Moyer. The point is clearly and boldly stated in the artwork.

Ever since the cave paintings of animals, humans have expressed deep interest in nature. Great landscape art evokes a sense of wonder with the scenes unfolding in front of the viewer. For me, the greatest interest lies in studies that place forces of nature in opposition. Generally, the work of the Hudson School captures this conflict for me.

Now, with the climate crisis, art is representing the conflict between the results of human activities and the forces of nature.

Toward this end, an Internet list entitled “Arts and Climate Change” investigates and informs readers of new and imaginative ways to understand the crisis at hand – through created works in various media that extend knowledge in a meaningful way.

See & share: https://artistsandclimatechange.com/

There also is a current exhibition, “One Tribe on One Planet,” at the Yocum Institute in West Lawn, Pennsylvania, presenting the artists’ conceptualization of this conflict very well. At the exhibit, one can see knowledge being absorbed or deepened on the part of the viewer. The exhibit designers interspersed sourced “Climate Facts” among the artworks, facts that relate to subjects of the pieces. This was powerful. (Exhibition open through June 27, 2019) Sometimes art, even when portraying a disaster, can be quite beautiful. The fear I had with portraying climate crisis is that beauty would undermine the message. My concern was unwarranted.

Over fifty years ago Rachel Carson wrote Silent Spring, a scientific study of the impact of humans on nature, especially due to the indiscriminate use of chemicals through herbicides and insecticides. Carson’s work is still powerfully articulate. Afterwards, in 1989, Bill McKibben wrote The End of Nature. McKibben’s thesis is that humans are impacting all aspects of nature and that the idea of natural forces acting alone is no longer true.

More recently, David Grinspoon wrote Earth in Human Hands: Shaping Our Planet’s Future (2014). Grinspoon posited an idea of a new geologic phase of earth history, “one in which the net activity of humans has become a powerful agent of geological change equal to the other great forces of nature that build mountains and shape continents and species.” The emerging term for this new epoch is ‘Anthropocene’ or ‘the age of humanity (x)’.”

A common theme of these works is that humans can learn about forces affecting the planet and could take actions to slow, halt, potentially reverse, or adapt to the trend.

Reversing the trend will take knowledge and the will to act on that knowledge. Scientists have established undeniable facts about the climate crisis. Reports are issued almost daily in a torrent of studies that attest to the changes taking place and the process of measuring those changes.

Simply being willing as a scientist to learn about global warming, rising sea levels, species extinction, pollution, etc. is insufficient. Science can be complex and confusing to the non-scientist. It takes the arts to translate scientific observations and projections into forms that can be understood by non-scientists. The target is essentially on modifying human behavior. But the appeal is also to the general population, a voting population, that can generate the collective political will to act.

Scientists can measure the levels of CO2 in the environment to specific parts per million and calculate dangerous thresholds that are rapidly approaching. The artist can interpret the findings and present them in visual, literary, or musical forms. The arts, then, are vehicles to communicate to the public the knowledge distilled through scientific measurement and experimentation.

With over thirty works of art in various media, the message of the “One Tribe on One Planet” exhibition was unambiguous. Each work examined various impacts of humans on nature.

The artwork ran the range of concrete to abstract. Among the most creative was the work entitled “No Fish” by artist Melody Moyer. The point is clearly and boldly stated in the artwork.

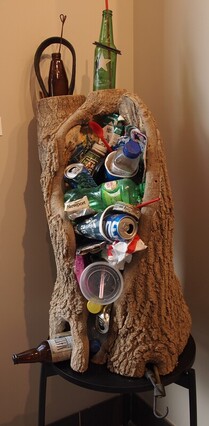

More subtle but equally effective is the work “Tree of Life Trashed,” a mixed media by Marcia Graff Rowe. It targets the effects of littering, a personal behavior that should be easily remedied.

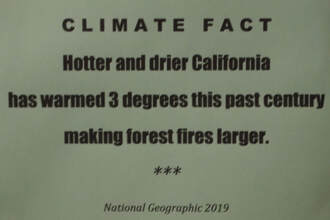

“Heat of the Night” by Lynn Millar visualizes the massive fires in Californian during the summer of 2018. The intensity and extent of the fires correlate to the increase in global temperatures. The climate fact card tells of the increase in temperatures.

All photographs by the author, John M. Lawlor, Jr.

All photographs by the author, John M. Lawlor, Jr. For my contribution, I installed a computer workstation that looped Amanda Gorman’s “Twenty-four Hours of Reality: Earthrise” every fifteen minutes. Gorman’s poetic analysis fits the arts concept very well. See: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwOvBv8RLmo

It is hoped that as works such as these and the dozens more in the exhibit are viewed either in person or via social media, a spirit of urgent activism will be fostered. The knowledge amassed via scientific inquiry will inform the public via the educational power of art. The “I’m not a scientist” excuse for denying that the climate crisis exists is no longer viable.

One does not need to be a scientist to understand. One simply has to be willing to learn.

It is hoped that as works such as these and the dozens more in the exhibit are viewed either in person or via social media, a spirit of urgent activism will be fostered. The knowledge amassed via scientific inquiry will inform the public via the educational power of art. The “I’m not a scientist” excuse for denying that the climate crisis exists is no longer viable.

One does not need to be a scientist to understand. One simply has to be willing to learn.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed